Wonder and the Good

This is an adapted transcript of Larry P. Arnn’s introduction to the course “Introduction to Western Philosophy,” which is available for free online from Hillsdale College.

Philosophy.

Everybody has a philosophy. In recent days, I’ve heard someone say they have a philosophy of grocery shopping amid the Coronavirus pandemic. People have philosophies about cars. They have philosophies about everything. We all know that word, and many of us use it… But what does it really mean?

Philosophy comes from two Greek words: Philos (love), and sophos (wisdom), and wisdom is a specific thing. It is one of the ultimate objects of human existence and indeed one of the ultimate objects of the universe. Wisdom is a quality of the intellect, the part of you that does the thinking, and it separates into two kinds.

Practical Judgment

The kind that we all practice all the time is what the classics, especially Aristotle, called practical wisdom, practical judgement, or prudence. Practical wisdom is a kind of knowing that seeks truth (wisdom has to be about things that are true), but it seeks truth amist the circumstances in which decisions are made and actions are taken. Those circumstances change all the time, and their momentary state has a big effect on what the decisions should be. If you mess that up, you’ll do the wrong thing.

Practical judgment looks at things that are swirling, and because they’re changing, you only know them while you’re looking at them. We all have to make these practical judgments because we have to live. Even dogs and wolves make choices to sustain themselves according to instinct.

But then there’s this other thing in us humans that complicates our choices: We can do something that seems necessary for our own survival, our own appetites, or our own glory, and then later we can feel bad about it (Aristotle says that human beings are the animals that can blush). We can be ashamed of ourselves. Human practical judgment involves something that stands outside the momentary circumstances and the ends that one is seeking and sits in judgment on them. That something is inside us, and we can’t get rid of it.

Well, Aristotle says there is one way that you can get rid of it. You could do the long, arduous work of turning yourself into a simply vicious person. Very few people do that, he says, just as very few people become fully virtuous people.

So, practical wisdom is dual-minded. It looks at the stuff that is moving all the time, but it keeps in mind some things that are outside this change - things that are even eternal. That part of intellectual virtue is one kind of wisdom.

Wisdom

The other kind is wisdom, simply, just by itself. And Aristotle in particular - he is great because he makes things clear and orderly, although they are complex sometimes - he says that wisdom is knowledge of things that never change. They stay the same for a long time - forever - and that means that once you know them, you know them. That is very valuable knowledge to have.

Also, mind you, it’s not particularly useful knowledge to have, because these unchanging things can only apply to what’s going on right now in our lives if we stop thinking about them for a minute and notice the circumstances we’re in and what we need and what we want. It might tell us what we ought to want, but those are different things.

And when you’re engaging in practical wisdom, you’re calculating. You’re trying to solve a problem. You’re looking for a sum. You’re looking for an answer. This is what I should do. And the truth that this process finds is true in those circumstances and for that decision and not true if the circumstances are different or even if it’s just later.

Whereas this wisdom, it actually is focused wholly on the thing that it looks at, and that thing has a dignity, because anything that is eternal is superior to anything that passes away. Hillsdale College is old - 175 years - and I like it very much that it is old, and I hope and expect that it will last for another 175 years and 175 years after that, and it looks okay right now as long as the country stays together, which I hope and pray. But the college is not eternal. It’s actually true that the things it seeks are eternal, and in regard to the college, those things are ends and the college is a means. Although it is a great dignity in itself and good for its own sake, it’s only good for its own sake because it seeks these eternal things.

Since they’re not of practical use in any given moment, these eternal things, one wonders, how does one get concerned with them? Why does one care? And there are two words I think are important to help figure that out. One word is good, and one word is wonder. Nathan is going to tell you a lot about those two things, and I’m going to tell you briefly what I think they are, and I’ll probably agree with Nathan.

The Good

First of all, good - it’s like philosophy, except even more - we all use that word. That’s good. In a couple of months, freshmen are going to show up here. We always love that. Everybody is coming back, but the freshmen are a special interest because they’re young and shy and funny, and we make fun of them, I confess. But it’s a great thing to ask them questions. So if you ask them, “Why’d you come here? Why did you do anything? Why do you intend to do anything?” You never have to ask more than two or three questions to get them to say, in some form or another, that the thing is good. Then we always say, “What is it for a thing to be good?”

Around here, you learn very fast not to say, “Well my opinion is…” because we always say we don’t care about that. We want to know what the thing is. It’s harder if you have to just say what it is. And don’t turn it into a question about yourself. What is this thing? Let’s give ourselves to this. Let’s try to figure it out.

Everything we do - all those operations that we engage with in practical judgment - they raise the question of the good. And that’s why the Socratic dialogues - they’re different from Aristotle. Plato wrote most of them. They all have in them this feature. Somebody’s doing something, and that implies that the thing is good, and Socrates that they might not know really whether it is or not or be able to explain why. That’s what gives rise to Socrates’ famous statement, “I know that I know nothing. And because of that, I know more than most people, because they think they know things.” He’s always doing that to people, and he reduces things relentlessly to the good.

So that question of the good is an immediate question, it’s implicit in all of our decisions, and we have to answer it because we act and because we have choices we don’t have to act in a certain way versus another way, and that question of the good points upward toward the ultimate good, the thing that would be a complete good, a perfect good.

We play sports around here. We like to win. You know why - they keep score in sports. We like to win the right way, because if we did something craven in order to win, that would be too bad, but there’s no complete good in sports. They’re representations of it, they’re suggestions of it, and if you admire people who do excellently in sports you often come to admire their characters too because the whole human being produces excellence, but that, too, is incomplete, because human beings don’t last forever, at least in their earthly form.

So this question of the good that’s implicit in all that we do invites us to think above ourselves. That comes up constantly. And it’s a pressing question.

Wonder

You will have in your life, I’m confident, experiences with friends, teachers, parents, and children, you’ll have golden moments when you have a really great talk about things. Just things. And it will lead up to ultimate things. And the feeling that comes from sharing that with somebody is very powerful. Aristotle describes that activity, when you have those conversations, as the highest human association, the ultimate form of friendship, which is the highest human association.

Another thing that leads us to the good, another word, is wonder. I wonder. It is wonderful. That means you can’t really account for it, and you only really talk about that with things that are puzzling, sure enough, but also beautiful. It can be any kind of thing. Around here, we have this experience all the time. Aha! Students learn something great, and everybody takes pleasure in it. Often, we learn it at the same time. We’ve worked to learn it, and then it fits together. You have seen an answer, but the process itself is also wonderful. Wow, wonder. Look at that. That’s a great thing to have happened. How’d it happen?

In other words, when we see beautiful, elevating, beckoning things and we can’t explain them, it leads us to think. If you see natural beauty - I think my favorite natural beauty might be Yosemite Valley - it makes you just stop and look, and then you begin to try and describe it, and it’s hard. How would you begin to encapsulate that? How could you do that justice with your own speech? It’s wonderful. And when we see things that are wonderful, they call us to think, and the most serious thinkers, the great philosophers, they try to give coherent accounts of all that, and that’s an enormous intellectual achievement.

I teach Aristotle here pretty often, and it’s always great when one does that. In fact, all the classes here are great. All the ones I teach are just a joy to me, and there are always moments in the classes where something emerges from our discussion based on the text usually that is some great and wonderful thing to know. Once you know that thing, you’re not finished. It calls you to think even more.

Now those two things, the good and wonder, those are why we’re interested in philosophy. I was going to read you a quote. In a dialogue called Theaetetus, Socrates says - Theaetetus by the way is a young mathematician, a brilliant young man, shown and introduced to Socrates as a man who’s going to go far, and you should talk to him - Socrates says to this young man, “I see, my dear Theaetetus, that Theodorus had a true insight into your nature when he said that you were a philosopher, for wonder is the feeling of a philosopher, and philosophy begins in wonder.”

What this young man said to him was that he found some things wonderful, which meant he can’t give a complete account of them. Philosophers are not people who possess wisdom, necessarily. They’re people who love it, and they are given to wonder.

Perfect Things

Now, another word about what we wonder about: Perfect things. How do we know what those are? Aristotle’s account is, you see a thing, you can see what kind of thing it is - it’s how we’re able to use common nouns, how we’re able to speak with each other - and by seeing what kind it is, you’ve acknowledged a standard to which it is supposed to conform.

Now, kinds of things can also be more perfect than other things. How do we tell if a thing if a thing is perfect? Well, there are qualities that it has (in Aristotle in particular). Things are higher if they are self-sufficient, if they’re complete unto themselves, if they don’t need anything else.

We human beings are obviously not that, although, Aristotle says, our highest activity is the contemplation of these wonderful things, and it takes huge qualities of soul, of intellect and character, to spend much time wondering, contemplating the beautiful things. He says that’s the most self-sufficient activity, although it’s not completely self-sufficient because he says if you have a friend who’s close to you who’s capable of that wonder that breaks out in class sometimes here, then you can do it better with the friend. Two is better than one, or three better than two.

So self-sufficient things are more perfect. Immaterial things are more perfect. What does that mean? That means if a thing is made out of matter, it sets a limit to it immediately.

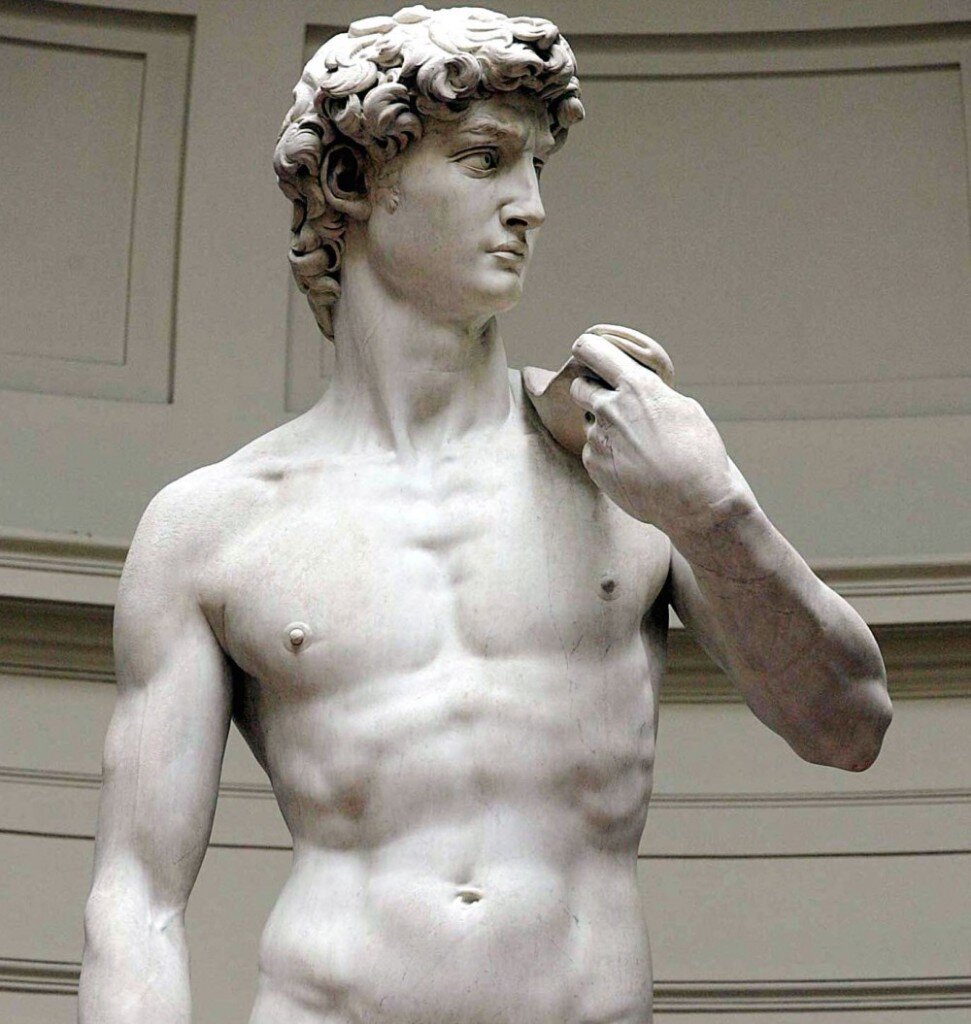

I like to describe my favorite statue, Michelangelo’s David - it’s not a very controversial choice because it is widely acknowledged to be one of the best, and it’s made of white marble, and that changes it. If it were bronze, it would be dark. And no - it’s made of white marble, and there’s a purity about that, and that’s right for the theme of this boy - unspoiled boy, it’s young David about the time of Goliath - and so he’s pure, and the material suggests that.

Now, Moses, Michelangelo’s statue of Moses, is nearby, and it’s grey marble, darker, stormy, the lawgiver. He looks very firm sitting in his seat. Thunder clouds around him, that kind of thing. And so, if it were white marble, like David, it wouldn’t be as adaptable to make Moses.

A third statue nearby in the same place in Rome is the Pieta - Jesus, broken, taken down from the Cross on the lap of his mother - and that’s in shades of off-white with touches of lavender. It’s very gentle.

Now the point is, those materials are very adaptable to the specific purpose to which they were put, but not necessarily to other purposes. Matter is a limiting factor as well as an enabling factor. So if something could get along without any matter, it would be more pure - something that lasts forever. That means it doesn’t decay, and that means it’s more perfect.

Since immaterial is good, what is it that’s knowable that’s not material? The answer to that is thoughts. Aristotle actually derives the argument that God is thought, but then what’s the thought thinking about? Do you see how you can sort of build up by a process of elimination to this point I’m about to make? God couldn’t have matter.

Perfect things don’t move. And the thing is, motion is not complete until it stops being motion. Motion is always a partial thing, so a perfect thing wouldn’t move.

Philosophy Leads to Theology

Immaterial. Wouldn’t move. Everlasting. Self-sufficient. Aristotle describes God as having those things, and God being a necessary deduction from the things we see around us if we think hard enough.

Nathan is going to tell you that the first theory in the Summa Theologica is whether there’s anything apart from reason that is necessary to know God, and the answer to that query is - it’s the very first one in that massive, wonderful achievement of a book - he says, yes, there are things apart from reason, but you can know a lot about it by thinking about it.

Thomas Acquinas was a Christian saint, of course, and the great recoverer and proponent of Aristotle in the Medieval world who had been largely lost in the West, and he resurrected him and got his works out there and wrote about him a lot, and he set out to reconcile Christianity with Aristotle’s thought of an unmoved mover. How would you reconcile that to a God who cares about us, is love, and acts and moves and creates? Well, that’s a big tall order to explain that, and Thomas Acquinas undertakes that in my favorite book by Thomas Acquinas the Summa Contra Gentiles, the sum of the arguments against the non-believers is how it translates, and in the first book - it’s about God, the first book is entitled “God” - in chapters 45-49, in there, he actually in about 15 pages describes how the Christian God is also an unmoving and entirely self-sufficient God.

Now, that’s a philosophical argument as well as a theological argument. And since philosophy is looking for the everlasting things, knowledge of the everlasting things and the accumulation of knowledge of those things by living your life right to accumulate that knowledge, you can see how it necessarily leads on to theology, and it does in Aristotle, a pagan, and it does in Thomas Acquinas, a Christian saint, and it would need to do that, I think, unless - and you’ll learn this from Nathan - in some modern philosophy, they chop philosophy off at the top. They actually decapitate it, and they say, “You can’t answer those questions anymore.”

What you can do - and this is a vast oversimplification, which is why I like it, I think it represents - what you can do is you can remake the world any way you want it and stop wondering about the highest things, and liberate your actions from that voice that talks to us all that explains to us we’d really rather be good, wouldn’t we, even if it might cost us our life. What if instead, all we do is give up on philosophy, answering the ultimate questions, and make it a tool of power, and that’s what happens in modern philosophy, I think.

Philosophy Will Make You Free

But that’s unsatisfactory, too, which means that modern philosophy can never fully triumph, no matter what one thinks. It can give rise - it has given rise to the great totalitarian regimes that can nearly conquer the world, to vast scientific injustices on enormous scale, and yet in the end, that won’t work.

I’ll close with my favorite quote from Winston Churchill. It’s in an essay he wrote called “Fifty Years Hence” - it’s one of his best, one of the most important things. He wrote it in the 1930s, and I’ll paraphrase a passage in that essay.

He says, imagine a race of beings who come 16 or 17 generations in the future, and imagine they’ve conquered nature. Imagine they can live as long as they want. Imagine they can have pleasures wider than any we can know. Imagine they can travel anywhere they want to go, including interplanetary. That’s a kind of dream of the modern world, isn’t it? And then Churchill asks, what would be the good of all that to them? What more would they know about the fundamental questions we must face - why are we here? What are we for? What should we do?

The life without philosophy is a despotic life. That’s how Winston Churchill knew that Adolph Hitler was a madman.

You should study philosophy. It will make you free.

Thank you.

Larry P. Arnn

President, Hillsdale College